According to their website, and I wasn't aware of this, the gallery houses the largest collection of British art outside of the United Kingdom. The collection started with a donation by Yale alumni, Paul Mellon, and the building itself was the last building designed by Louis I. Khan, who was responsible for much of the design for the art gallery across the street. The gallery opened to the public in 1977 (https://britishart.yale.edu/about-us). I was surprised that there was an entire separate building for primarily British art that was not included in the main art gallery across the street. Because this was my first time visiting, and I wanted to make sure I could photograph pieces, I grabbed a map at the front desk and checked out the layout of the museum. It's quite a compact layout on each floor. The lobby of the building conjures up imagery more akin to the lobby of a corporate bank headquarter than an art gallery. There is an interesting industrial-looking stairwell through the middle of the building. The fourth floor gallery view is pretty snazzy also.

According to their website, and I wasn't aware of this, the gallery houses the largest collection of British art outside of the United Kingdom. The collection started with a donation by Yale alumni, Paul Mellon, and the building itself was the last building designed by Louis I. Khan, who was responsible for much of the design for the art gallery across the street. The gallery opened to the public in 1977 (https://britishart.yale.edu/about-us). I was surprised that there was an entire separate building for primarily British art that was not included in the main art gallery across the street. Because this was my first time visiting, and I wanted to make sure I could photograph pieces, I grabbed a map at the front desk and checked out the layout of the museum. It's quite a compact layout on each floor. The lobby of the building conjures up imagery more akin to the lobby of a corporate bank headquarter than an art gallery. There is an interesting industrial-looking stairwell through the middle of the building. The fourth floor gallery view is pretty snazzy also.  |

| Fourth Floor Portrait Gallery |

|

| Fourth Floor Looking Down |

|

| First Floor Looking Up |

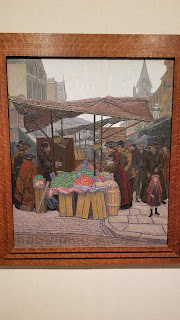

This painting by Charles Ginner had caught my attention as I walked among many fine examples of landscape, portraits, and scenery depicting everyday activities in the lives of the British population. Entitled Fruit Stall, King's Cross, it displays a scene in a busy British marketplace in King's Cross. Ginner, who according to the painting's informational panel, was originally an architect who trained in Paris. The piece reminded me a lot in terms of painting style of Van Gogh's The Night Café. There is this almost heavy-handed weight to the paint, much like the gratuitous globs Van Gogh used in his composition. I was interested with the outline of the painting's subjects also, as this was a similar quality between both paintings.

This painting by Charles Ginner had caught my attention as I walked among many fine examples of landscape, portraits, and scenery depicting everyday activities in the lives of the British population. Entitled Fruit Stall, King's Cross, it displays a scene in a busy British marketplace in King's Cross. Ginner, who according to the painting's informational panel, was originally an architect who trained in Paris. The piece reminded me a lot in terms of painting style of Van Gogh's The Night Café. There is this almost heavy-handed weight to the paint, much like the gratuitous globs Van Gogh used in his composition. I was interested with the outline of the painting's subjects also, as this was a similar quality between both paintings.  The floor also housed an exhibit entitled Captive Bodies: British Prisons. There were sketches, paintings, floor plans, and miscellaneous crime-related record books on display. Two pieces in this exhibit caught my attention more than any of the others. The first was entitled The Prisoner by Joseph Wright of Derby, painted from 1787-1790. I was fascinated in viewing this painting at the odd perspective it gives to a British prison. We see prisons as small, confining cells. Wright shows this particular prison cell as very cavernous, with a small, lonely prisoner in isolation. To me, there is irony in this scale; the size of the prison itself would give the inmate a false illusion of freedom due to the mobility, but ultimately, he is still a prisoner.

The floor also housed an exhibit entitled Captive Bodies: British Prisons. There were sketches, paintings, floor plans, and miscellaneous crime-related record books on display. Two pieces in this exhibit caught my attention more than any of the others. The first was entitled The Prisoner by Joseph Wright of Derby, painted from 1787-1790. I was fascinated in viewing this painting at the odd perspective it gives to a British prison. We see prisons as small, confining cells. Wright shows this particular prison cell as very cavernous, with a small, lonely prisoner in isolation. To me, there is irony in this scale; the size of the prison itself would give the inmate a false illusion of freedom due to the mobility, but ultimately, he is still a prisoner. The second piece that shares a similar theme is a sketch by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. The Staircase With Trophies, Plate VIII is part of a series he produced called Imaginary Prisons. Piranesi's piece is similar in the sense that it portrays this massive, though unrealistic, prison that dwarfs the inmates with many balconies, staircases, and hallways, allowing for mobility to provide a false sense of freedom. The inmates are portrayed as engaged in a futile effort to find a way out of their prison.

The second piece that shares a similar theme is a sketch by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. The Staircase With Trophies, Plate VIII is part of a series he produced called Imaginary Prisons. Piranesi's piece is similar in the sense that it portrays this massive, though unrealistic, prison that dwarfs the inmates with many balconies, staircases, and hallways, allowing for mobility to provide a false sense of freedom. The inmates are portrayed as engaged in a futile effort to find a way out of their prison. I liked the inclusion of some more informative additions to the collection such as the record book of offenses for inmates. The book gives insight into the criminal justice system in a much older time. In some ways, it was far stricter (I mean, come on, three months for stealing a purse? Nowadays that gets a slap on the wrist and community service, depending on your legal representation).

|

| Cue the Law and Order SVU *DUN DUN* |

George Shaw is a British artist born in Coventry. Most of the work on display in the exhibit was from either one series or multiple related series (honestly, at the time of writing I can't recall.). There is a commonality among his titles and settings, each painting that I had stopped to look over pertained to a specific time of day on a Christian high holiday. His style of painting gives his imagery a very natural, photorealistic look (truthfully, the first few that I had viewed I had a hard time determining if this was a photograph exhibit or paintings). I enjoyed his exhibit because of my penchant for the dystopian (I'm a huge fan of bleak fiction. One of my favorite novels is Nevil Shute's On the Beach)and photography by individuals who engage in urban exploration (this is pretty much people who just trespass in abandoned and condemned properties such as old psychiatric hospitals, schools, and theaters. It is art in the same context that though graffiti is illegal, some of that work takes much skill to create). The example shown is entitled Ash Wednesday 7:00 am. I think this one piece of the few that I snapped best conveys that bleak emptiness that I saw in his paintings. I think the real reason for the emptiness is more so because these are areas of England that are not tourist-y destinations and that they are probably from photos taken very early in the morning. To me, though, it is sunrise on the day after the apocalypse.

George Shaw is a British artist born in Coventry. Most of the work on display in the exhibit was from either one series or multiple related series (honestly, at the time of writing I can't recall.). There is a commonality among his titles and settings, each painting that I had stopped to look over pertained to a specific time of day on a Christian high holiday. His style of painting gives his imagery a very natural, photorealistic look (truthfully, the first few that I had viewed I had a hard time determining if this was a photograph exhibit or paintings). I enjoyed his exhibit because of my penchant for the dystopian (I'm a huge fan of bleak fiction. One of my favorite novels is Nevil Shute's On the Beach)and photography by individuals who engage in urban exploration (this is pretty much people who just trespass in abandoned and condemned properties such as old psychiatric hospitals, schools, and theaters. It is art in the same context that though graffiti is illegal, some of that work takes much skill to create). The example shown is entitled Ash Wednesday 7:00 am. I think this one piece of the few that I snapped best conveys that bleak emptiness that I saw in his paintings. I think the real reason for the emptiness is more so because these are areas of England that are not tourist-y destinations and that they are probably from photos taken very early in the morning. To me, though, it is sunrise on the day after the apocalypse. The fourth floor has so much to show in terms of portraits, it was a lot to take in. One of the interesting commonalities that I viewed among the pieces was that many of them were done during the period of colonial expansion of the British empire, so you see many works displaying either West Indies servants/slaves or Indian individuals in the same regard. For every painting that displayed this individuals in this context, there was just as many portraying the cultural representative on display in a much more dignified manner.

Portrait of a Gentleman and an Indian Servant is one such example of this portrayal of colonial dominance over the indigenous people. The painting is by Arthur William Devis in 1785. According to the information provided next to the painting, Devis was shipwrecked east of the Phillipines and traveled to Calcutta in 1784. Much of his work was portraits of British colonialists in the region. This one is one of the examples that I mentioned regarding portrayal of the Indian population in servitude. We have the servant attending the unknown man, but he is deliberately not looking his master in the eye.

Portrait of a Gentleman and an Indian Servant is one such example of this portrayal of colonial dominance over the indigenous people. The painting is by Arthur William Devis in 1785. According to the information provided next to the painting, Devis was shipwrecked east of the Phillipines and traveled to Calcutta in 1784. Much of his work was portraits of British colonialists in the region. This one is one of the examples that I mentioned regarding portrayal of the Indian population in servitude. We have the servant attending the unknown man, but he is deliberately not looking his master in the eye. This piece is a contrasting example, showing the Indian culture in a more positive representation. Thomas Hickey painted this image entitled Purniya, Chief Minister of Mysore in 1801. The side placard tells the story that Purniya was the minister to Tipu, who was a French-backed sultan of Mysore. Purniya was installed by the British as administrator when Tipu was killed. this painting was a fine example of the dignity that the Indian culture maintained while under imperial rule. The minister is very refined looking, attending dutifully to paperwork, with lady justice looking onward in the background.

I think out of all the museums and pieces I have visited, viewed, and analyzed so far, none have grabbed my attention as much as the monstrosity adorning the wall in Yale Center for British Art.

John Martin. The Deluge. 1855. Good God, where to begin with this one? I rounded the corner and turned and saw this black behemoth, and my jaw dropped. As I've said numerous times in previous posts, I'm not a religious person, but I tend to gravitate towards the paintings because of the heavy symbolism. Most times when you see works of religious art, you see very bright vibrant, victorious imagery of Christ or the saints, but this painting and its take on the Hebrew variation of the flood myth is, raw.

I haven't been able to find much written about Martin on the internet outside from a Wikipedia biography. John Martin was an English born painter who did most of his work during the Romanticism period of philosophical thought and art, and it shows. This painting conveys that notion Edmund Burke described as the sublime, this feeling of terror and awe simultaneously. He was a deist, who believed that the natural world was enough to determine divine creation.

What I loved about this painting is the fact that we are seeing the other side of the story. We are aware of the Biblical account of Noah and the Great Flood; how the righteous and the creatures of the earth were spared and the wicked were washed away and destroyed. The painting shows the horror that those remnant caught unprepared faced, and there is so much in terms of narrative taking place in this painting (grab a snack this is going to take awhile).

Smack dab in the middle of the painting is an individual who assumedly is speaking blasphemy regarding the condition they have found themselves. The man is standing, while many around him fall in despair, hands raised towards the heavens, perhaps in defiance, perhaps in petition to his own pagan gods. An individual attempts to cover his mouth as he is struck by what appears to be lightning.

Smack dab in the middle of the painting is an individual who assumedly is speaking blasphemy regarding the condition they have found themselves. The man is standing, while many around him fall in despair, hands raised towards the heavens, perhaps in defiance, perhaps in petition to his own pagan gods. An individual attempts to cover his mouth as he is struck by what appears to be lightning.  |

| Close up of the Bottom portion.

|

Off to the left of the painting lies another portion of crowd. Again, more individuals in anguish over their impending doom. We can actually see towards the upper left a woman plunging off the cliff, infant in hand. It was ironic to see such hopelessness conveyed through a religious painting.

The part of the painting that captured my interest the most was the two

individuals dangling over the precipice of black nothingness. I'm assuming the backstory to this is that they are lovers, partners, however you want to name them. I didn't take their locked gaze as relief that he has rescued her; I saw this as the moment before a lover's suicide pact was initiated, and I think that just compounds on the tragedy unfolding before us.

individuals dangling over the precipice of black nothingness. I'm assuming the backstory to this is that they are lovers, partners, however you want to name them. I didn't take their locked gaze as relief that he has rescued her; I saw this as the moment before a lover's suicide pact was initiated, and I think that just compounds on the tragedy unfolding before us. And what of our righteous individual Noah and his family, who were spared in the famed Ark? Martin has not forgotten the inclusion of this detail in his disaster, however, one must have a keen eye to notice their location, and with good reason.

Seated far above the rising floodwaters, high above a mountaintop sits the Ark. Noah and his family are very safe and very separated from the events unfolding below them. Martin placed Noah, in a sense, in a position of judgement over those who have been doomed to destruction. Normally in religious iconography we are meant to sympathize with the martyr, the saint, or the Savior. I don't believe the viewer is meant to side with Noah in this rendition of the myth; there is too much tragedy unfolding from the perspective of the remnant of humanity that was not spared. I think we put ourselves in their shoes and wonder why as they undoubtedly have.

Seated far above the rising floodwaters, high above a mountaintop sits the Ark. Noah and his family are very safe and very separated from the events unfolding below them. Martin placed Noah, in a sense, in a position of judgement over those who have been doomed to destruction. Normally in religious iconography we are meant to sympathize with the martyr, the saint, or the Savior. I don't believe the viewer is meant to side with Noah in this rendition of the myth; there is too much tragedy unfolding from the perspective of the remnant of humanity that was not spared. I think we put ourselves in their shoes and wonder why as they undoubtedly have.I enjoyed my visit to the Yale Center for British Art. For a weekend, there was a very light crowd, which allowed me to take my time in viewing the pieces that I chose to spend more time with. I wished that the resource and rare text study areas had been open and available for viewing. I've always enjoyed visiting Beinecke Manuscript Library. If anybody is still undecided on their remaining museum visits for the mod, I suggest giving this one a trip.

Your enthusiasm for The Deluge is palpable. Again, great job in conveying your direct perceptions of the piece(s). It is clear that you are getting much from encountering the actual works in person... which is the whole point of setting up the class this way. smiled when you said, "(grab a snack this is going to take awhile)"

ReplyDeleteWell done!